Will our baking future include eggless pavlovas, cheeseless cheese cakes, or sponge cakes minus wheat flour?

Those of us with family members who suffer food allergies may be accustomed to getting creative in the kitchen, however, as our climate and environment continues to change, it is inevitable that for most of us, our diets will need to change to reflect food availability and affordability.

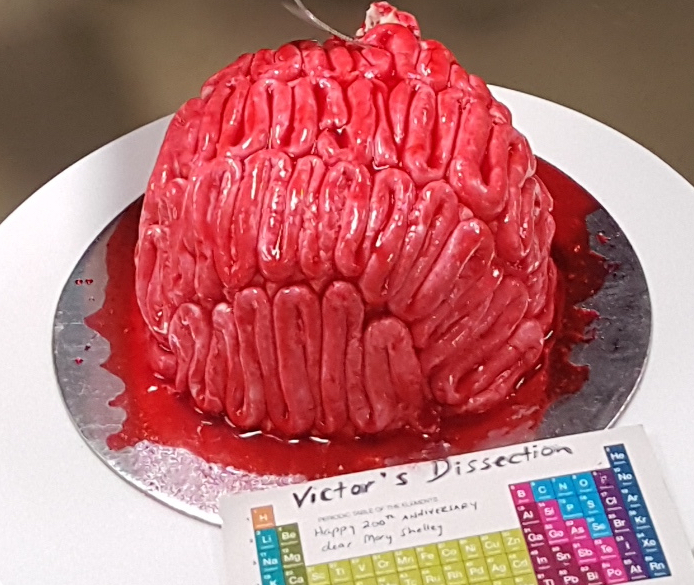

With this possible future in mind, during Science Week 2020, we challenged bakers to make the impossible possible: to bake some treats omitting ingredients that may be scarce in the future!

The Challenge

This Possible Impossibles Bake Off challenged wizards with the spatula and budding kitchen chemists to create a Science Week 2020 morning tea treat without wheat flour, eggs, dairy, or sugar.

Recipes and winning entries will be listed here shortly.

Humanity’s Future Food Challenge

There is a myriad of threats to the global food supply from pathogen infestations in crops and livestock to water shortages and climate change. By 2050, the UN projects that we will have nearly 10 billion people on the planet, which is many more mouths to feed. The Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that we need to increase our food production by about 40% by 2030 and 70% by 2050 to support this population growth. Population growth also eats into good quality farming land as urbanisation and cities spread out.

Agricultural practices themselves can be a threat to the changing climate. Many of us are aware of our carbon emissions, but methane and nitrous oxides are additional greenhouse gases predominantly produced in agriculture. Climate change and increasing greenhouse gas emissions have resulted in increased intensity and frequency of extreme weather events that impact crops.

The agriculture industry also takes up much of our fresh water supply – up to 80 or 90% of the current water supply in some parts of Asia and Africa. Water consumption varies from food to food. For example, it takes 13 litres of water to produce a tomato, 140 litres to make a cup of coffee, and a 100g chocolate bar could take up to 2,400 litres!

With dwindling global water resources and arable land, increased pollution and a changing climate, and the migration of pests, the outlook on our food security is not bright – but it is not all doom and gloom either. Due to advances in surveillance, biotechnology, and international cooperation, we can better track and address plant and livestock diseases, and create nutritional foods with alternative ingredients.

At Risk Foods

Here we identify some “at risk” foods that we might not be able to use in our future baked goods – so be creative and work out ways to get around potential shortages.

Please note that, while this content is based on scientific fact and research studies, it does also involve speculation on our part.

Wheat/Grain

Extreme weather conditions, such as heavy rainfall and consequent floods, have contributed to a severe outbreak of desert locust. In late 2019, there were reports of massive swarms of desert locusts are eating their way through East Africa, which have subsequently expanded from the Arabian Peninsula into western Asia. Locusts move in swarms of up to 50 million, can travel nearly 150 kilometres a day, and lay as many as 1,000 eggs per square metre of land – a force to be reckoned with.

Extreme weather conditions, such as heavy rainfall and consequent floods, have contributed to a severe outbreak of desert locust. In late 2019, there were reports of massive swarms of desert locusts are eating their way through East Africa, which have subsequently expanded from the Arabian Peninsula into western Asia. Locusts move in swarms of up to 50 million, can travel nearly 150 kilometres a day, and lay as many as 1,000 eggs per square metre of land – a force to be reckoned with.

In May 2020, farmers in Pakistan faced the worst locust plague in recent history, leading to fears of long-term food shortages. The Pakistani government declared a national emergency as swarms of locusts descended to decimate crops, causing billions of dollars of damage.

The main casualties have been wheat, mustard and cotton crops, although many other plants crops have also been decimated. The cost of flour and vegetables had already risen by 15% this year in Pakistan, and the locust infestation could make even basic food staples such as these unaffordable.

Australian plague locusts typically inhabit the far north of New South Wales, and adjacent areas of Queensland and South Australia in relatively low in numbers. But under favourable weather conditions, they also can multiply and spread out in large swarms to agricultural areas in southern Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia, causing severe damage to pastures, field crops and vegetables. The Australian plague locust prefers to feed on grasses and/or cereal crops such as wheat. Crops at most risk include wheat, barley, and especially oats.

Not only do wheat and barley farmers have to worry about locusts, another major threat is wheat rust, a fungal disease. In the 1950s, wheat rust destroyed 40% of crops in North America, but since then, strains of wheat were cultivated to be resistant to the fungi. However, in 1999, a new strain of rust (Ug99) emerged in Uganda, which was a more potent and damaging strain and most wheat planted in the area was susceptible to disease. The rust has since spread through to Kenya, Ethiopia and the Middle East. If it were to affect major agricultural areas in Australia, Asia or America, the results would be devastating. We would all be on a gluten free diet!

Eggs

Earlier this year Australian consumers feared an egg shortage; however the shortage was purely demand driven, and not due to a supply shortage. But will we have to worry about a shortage of eggs in the future?

Earlier this year Australian consumers feared an egg shortage; however the shortage was purely demand driven, and not due to a supply shortage. But will we have to worry about a shortage of eggs in the future?

Whilst the humble egg has a relatively small planetary footprint, as more people are concerned for animal welfare, the demand for farmers to produce free-range eggs is rapidly increasing. Caged hen farms with high protein feed and near-constant lighting push hens to lay around 500 eggs annually (as opposed to wild hens that lay about 20). A reduction in the egg number produced per hen, combined with an increase in the farming land required to supply demand, is likely to see substantial increases in egg prices. Egg Farmers of Australia Chief Executive estimates that a regulated ban on caged eggs rolled over the next decade would increase the cost of eggs by 30%. This could make the average sponge cake made with five or six eggs quite a luxury!

An additional threat to the poultry industry is influenza. Free-range chickens that access outdoor areas are susceptible to catching the flu from wild birds (as well as predators and climate extremes). A bird flu outbreak in the US in 2015 more than doubled egg prices across the country. The flu, being highly contagious, can easily infect a shed full of chickens – which could be something like half a million birds.

Dairy

A study by the Dairy Australia in 2015 showed that the dairy industry accounted for around 10% of agricultural greenhouse gases (and about 2% of national emissions). The good news is that the levels of methane, a greenhouse gas, produced by dairy cows has been shown to correlate with diet, and therefore emissions could be reduced by improving the quality of the cows’ diets. Cows allowed to graze on high quality pastures produced around 270 – 350 g methane/cow/day compared to those on poor quality pasture or feeds at 370 – 450 g methane/cow/ day. However, with increasing population size and demand for housing, grazing land is a precious commodity.

A study by the Dairy Australia in 2015 showed that the dairy industry accounted for around 10% of agricultural greenhouse gases (and about 2% of national emissions). The good news is that the levels of methane, a greenhouse gas, produced by dairy cows has been shown to correlate with diet, and therefore emissions could be reduced by improving the quality of the cows’ diets. Cows allowed to graze on high quality pastures produced around 270 – 350 g methane/cow/day compared to those on poor quality pasture or feeds at 370 – 450 g methane/cow/ day. However, with increasing population size and demand for housing, grazing land is a precious commodity.

Water scarcity linked to a climate changed world will also impact the dairy industry, affecting the amount of water available for animal drinking, feed crops, and product processing. This, and the prediction that increases in average temperatures will increase animal water consumption by a factor of two or three, may translate into reduced herd numbers, and mean less milk for us!

Sugar

With conflicting outcomes of studies into the impacts of climate change on the sugarcane industry, no final conclusions have been made. The sugarcane plant can adapt to different environmental stresses but has high vulnerability extreme weather events and frost. Temperature stress limits sugarcane plant growth, productivity and metabolism, reducing the amount of sugar available.

With conflicting outcomes of studies into the impacts of climate change on the sugarcane industry, no final conclusions have been made. The sugarcane plant can adapt to different environmental stresses but has high vulnerability extreme weather events and frost. Temperature stress limits sugarcane plant growth, productivity and metabolism, reducing the amount of sugar available.

At first glance, it may appear that global warming may be beneficial for sugarcane, as temperatures below 15°C limit the cultivation of sugar, and temperature increases in the winter months improves yield and likely reduces the incidence and severity of frost. However, higher temperatures overall have a negative effect on the sprouting and emergence of new sugarcane plants, ultimately reducing the plant population. Additionally, high overnight temperatures reduce the levels of sugar in the sugarcane. An increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration also affects the growth of most plants as carbon dioxide is the main contributor to photosynthesis. Sugarcane uses a slightly different photosynthesis mechanism and may become more vulnerable to increased competition from weeds. In fact, uncontrolled annual summer weeds result in a 15% reduction in commercial sugar production.

Sugarcane smut, one of the most serious diseases of sugarcane, is also likely to increase under high temperature conditions. Discovered for the first time in Western Australia, smut is now present in all regions of the Australian sugar industry. The disease is caused by a fungus, and kills susceptible sugarcane plants – and the world loses a little more sweetness.

Recipes to Try

Vietnamese Cassava Cake (recipe submitted by Suong Nguyen)

Ingredients:

250 ml coconut milk

1 bag of frozen grated cassava (usually ~450g/16oz)

120 g palm sugar (2x round cakes)

100 ml water

Methods:

- Dissolve palm sugar in water on a stove, reduce to half the volume. Set aside to cool.

- Mix thawed cassava with coconut milk.

- Add (slightly cooled) palm sugar. Still well until combined.

- Pour mixture into a standard cake tin and bake in oven at 180°C for ~20-30 minutes (cake will turn transparent and then golden brown when done).

Chocolate Cake (recipe submitted by Catriona Nguyen-Robertson)

Ingredients:

3 cups oat flour

1 1/3 cup cocoa powder

2 tsp baking soda

1/2 tsp salt

1 1/4 cup water

1 cup non-dairy milk (soy, almond, coconut)[1]

1/4 cup + 2 tbsp coconut oil

1/2 cup coconut sugar

1/2 maple syrup

2 tsp vanilla extract/essence

Icing:

1/2 cup maple syrup/melted honey[2]

1/2 cup cocoa powder

1/4 cup coconut oil

Methods:

- Sift oat flour, cocoa powder, baking soda and salt and give them a little mix

- In a separate bowl, add hot water to coconut oil and mix until dissolved

- Mix the other wet ingredients (milk, maple syrup and vanilla) in with the coconut oil + water, then pour it into the dry ingredients bowl

- Sift coconut sugar into the bowl

- Mix until well incorporated. If lumpy, whisk with an electronic beater

- Coat baking pan(s) with vegan butter, olive oil spray, or melted coconut oil

- Bake in the oven at 180°C for ~30 minutes (or until a tester comes out dry)

- Leave in pan for a few minutes after removing from the oven, then transfer to a cooling rack (use a plastic knife to help if the cake sticks)

- Completely cool the cake before icing it

- To make icing, stir melted coconut oil and maple syrup/honey and sift in cocoa powder

[1] Coconut milk yields a richer, more dense texture, however the cake is fairly rich with soy or almond milk.

[2] Use maple syrup only to be vegan.