Detection Dogs

Written by Catriona Nguyen-Robertson

Written by Catriona Nguyen-Robertson

From Border Collie bodyguards to puppies on patrol, dogs are helping Zoos Victoria protect some of our most threatened species.

Australia is facing an extinction crisis: as at 2019, a total of 1790 species of plants and animals are threatened with extinction. Additionally, the recent devastating bushfire tragedy claimed the lives of an estimated 1.25 billion animals. Zoos Victoria are now bringing in dogs to join us in the fight against extinction.

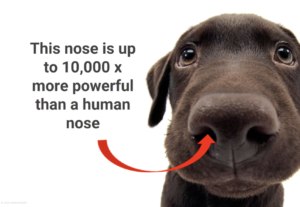

Olfaction is a dog’s primary sense. Dogs have over 300 billion olfactory receptors in their nose in contrast to our 5 billion, providing them with a sensitivity to smells up to 10,000 times greater than ours. In addition, dogs smell in stereo, having the ability to smell through each nostril individually. Dogs can therefore use their superior sense of smell to help locate and monitor threatened species that may be difficult for us to find using sight and hearing alone.

Olfaction is a dog’s primary sense. Dogs have over 300 billion olfactory receptors in their nose in contrast to our 5 billion, providing them with a sensitivity to smells up to 10,000 times greater than ours. In addition, dogs smell in stereo, having the ability to smell through each nostril individually. Dogs can therefore use their superior sense of smell to help locate and monitor threatened species that may be difficult for us to find using sight and hearing alone.

Dr La Toya Jamieson is a canine specialist at Zoos Victoria, assisting with the Fighting Extinction Detection Dog Program. She first saw wildlife detection dogs in action in South Africa and was excited to return to Australia to complete Honours and a PhD at The University of Queensland on this unique method of wildlife monitoring. Over a period of nine months, she trained and cared for twelve dogs herself, including Labradors, Border Collies and Greyhounds. Her research shows that, overall, it is the relationship between the dog, trainer and handler that has the greatest impact on a dog’s detection abilities, rather than its breed. Every dog is different and can perform differently with a different handler. In fact, in the US even a Chihuahua has got involved in searching for the Oregon Spotted Frog – after being carried up a mountain in a backpack!

La Toya’s research into the relationship between humans and wildlife detection dog teams interested Naomi Hogdens, a Conservation Detection Dog Officer at Zoos Victoria. Naomi investigated the effects of different training models on the dog-human relationship in the Anthrozoology Research Group Dog Lab at La Trobe University. She works with PhD candidate, Nick Rudder, who is using citizen science in detection. The Dog Lab trains local community volunteers and their dogs in conservation detection, relying on the strong bond between dogs and their owners.

For seven weeks, dogs were trained to memorise the odour of the Alpine Stonefly (Thaumatoperla alpina), a highly endangered insect in alpine regions. While brightly coloured, they are difficult to find as they live in water, buried under cobbles, boulders and the stream bed, only emerging as adults for a few months as adults to reproduce. Initial training introduced the dogs to the odour of the Alpine Stonefly with water samples from the Bogong High Plains, Mount Buller, and Mount Stirling containing trace amounts of stonefly DNA (such as cells shed from the insect). Following their training, three dogs and their volunteer handlers successfully surveyed a site at Falls Creek, where the population is less of a concern. In preliminary trials, the three dogs have since detected the Stirling Stonefly, a related stonefly species that lives in Mount Buller and Mount Stirling, suggesting that detection dogs can transfer their conservation training from one species to another. It also is the first instance in Australia where dogs have been trained to sniff out the animals themselves, rather than animal nests or faeces.

Working closely with La Toya and Naomi, Chris Hartnett, Threatened Species Project Officer, has led the strategic planning and implementation for the Zoos Victoria’s Detection Dogs program since 2016. The Program’s aim is to develop a “Dog Squad” to assist in field surveys of threatened species such as the Baw Baw Frog and Plains-wanderer bird. Successful detection of koala scat on Stradbroke Island and spotted-tailed quoll scat in NSW, gives Chris hope that detection dogs are better at detection and cover more ground more quickly than humans. But among all these successful stories, there tended to be a focus on searching for mammals – it was unheard of to search for amphibians.

Working closely with La Toya and Naomi, Chris Hartnett, Threatened Species Project Officer, has led the strategic planning and implementation for the Zoos Victoria’s Detection Dogs program since 2016. The Program’s aim is to develop a “Dog Squad” to assist in field surveys of threatened species such as the Baw Baw Frog and Plains-wanderer bird. Successful detection of koala scat on Stradbroke Island and spotted-tailed quoll scat in NSW, gives Chris hope that detection dogs are better at detection and cover more ground more quickly than humans. But among all these successful stories, there tended to be a focus on searching for mammals – it was unheard of to search for amphibians.

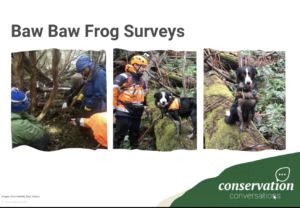

The first target was the tiny, brown Baw Baw Frog, that buries up to 30 cm in mud on the Baw Baw Plateau. Surveys are typically conducted by listening out for calls of the male frogs, without picking up females and young. With the help of a dog trainer, two brother Border Collies, Uda and Rubble, were trained to sniff out skin swab samples followed by the frogs themselves. By day two of training, Uda could select accurately pick a container with frog skin swabs. The two dogs were then taken into the field and found six Baw Baw Frogs, thoroughly surveyed the challenging terrain in a way humans could not.

In addition to pioneering the use of detection dogs to monitor amphibian and bird populations, the Zoos Victoria program aims to train dogs to cross-recognise species. Access to samples for training has remained one of the biggest hurdles in conservation. If dogs could recognise the scent of endangered species after being trained on the scent of more common, related species, this would be a game changer. Melbourne Zoo amphibian specialist, Dion Gilbert, works with multiple threatened frog species and is exploring the idea of “scent generalisation” – using common frog scents to train dogs to find rare and endangered species.

‘My sense is that you can find just about anything with detection dogs as long as you can obtain the samples,’ says Chris.

As well as in conservation, detection dogs have great potential to aid in animal management. The team is training dogs to smell differences in Tasmanian Devil scat depending on when they are receptive to mating or lactating. Tasmanian Devils dislike being handled by humans, and therefore training dogs to sniff their faeces less invasive. By knowing when females are lactating, handlers can ensure that they provide sufficient nutrients in the diet. This idea could be expanded for multiple species being bred in captivity to limit the amount of guess work involved when caring for them.

As well as in conservation, detection dogs have great potential to aid in animal management. The team is training dogs to smell differences in Tasmanian Devil scat depending on when they are receptive to mating or lactating. Tasmanian Devils dislike being handled by humans, and therefore training dogs to sniff their faeces less invasive. By knowing when females are lactating, handlers can ensure that they provide sufficient nutrients in the diet. This idea could be expanded for multiple species being bred in captivity to limit the amount of guess work involved when caring for them.

A very important focus for the Detection Dog Program is welfare – of the dogs, the threatened species being detected, and other wildlife in the search areas. Currently there are two dogs in the team, Kip and Roy, keeping it small until the program grows. The Detection Dog Officers have to balance the numbers of dogs ideal for surveys with how many they can handle. The dogs love the challenge, regarding detection as a game, and the team loves working with them.

‘We are stretching the boundaries of people’s thinking,’ says Chris. ‘People are not surprised that dogs have a strong sense of smell, but our Detection Dogs Program is expanding on that.’

The Dog Squad is changing the game for threatened species conservation. If an animal is in hiding or humans do not happen to walk past it, animals can be missed, giving a distorted view of the prevalence of endangered populations. With their superior sense of smell, Detection Dogs are able to use a highly effective and non-invasive approach to provide evidence of threatened species in Victoria and their population distribution. According to Chris, “the sky is the limit for this program!”

Sign your dog up for the Dog Lab program

Information contained in this story was taken from the Zoos Victoria Conservation Conversation, ‘Conservation dogs: Sniffing out threatened species’ Watch this conversation

Images – Top image (stock image – Josh Hild, Pexels). All other images (Conservation Conversations, Zoos Victoria)