Wild DNA: A World-First DNA Test

Science is for all

Science is knowledge. Knowledge is for everyone. Our planet is for everyone.

Science for All is a not-for-profit organisation that encourages everyone to get involved in protecting and restoring our land and biodiversity. They teach people about our natural heritage and how to monitor critically endangered animals.

Knowledge takes many forms. Many people confuse “scientific knowledge” with the scientific method itself, which is merely one, specific way of asking questions. But there are different ways that people understand the world around them, including the scientific method and sharing stories (including indigenous knowledge and oral history).

Teaching people how to ask a question can be the most simple, most profound or the most complex thing we can do as a species. Questions like ‘why?’ and ‘why not?’ are powerful. Science for All encourages people to ask and answer the question “How can we best protect and restore our natural heritage?”

Australia is facing an extinction crisis. We have the fourth-highest level of animal species extinction in the world. In 2019, a total of 1790 species of plants and animals were endangered or threatened with extinction. Additionally, the recent devastating bushfire tragedy claimed the lives of an estimated 1.25 billion animals. This affects our land and our country, and so we should therefore play a part in its restoration.

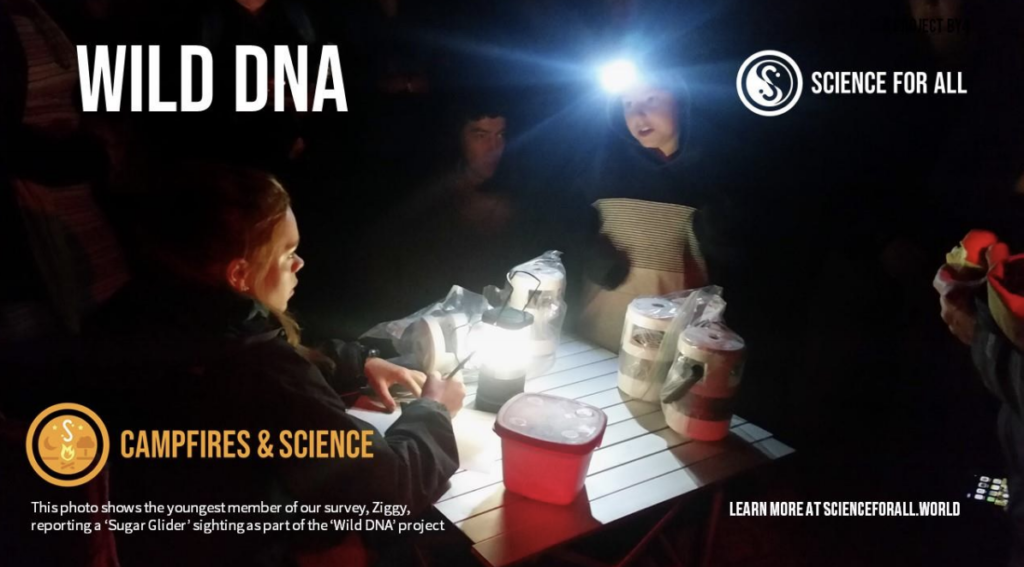

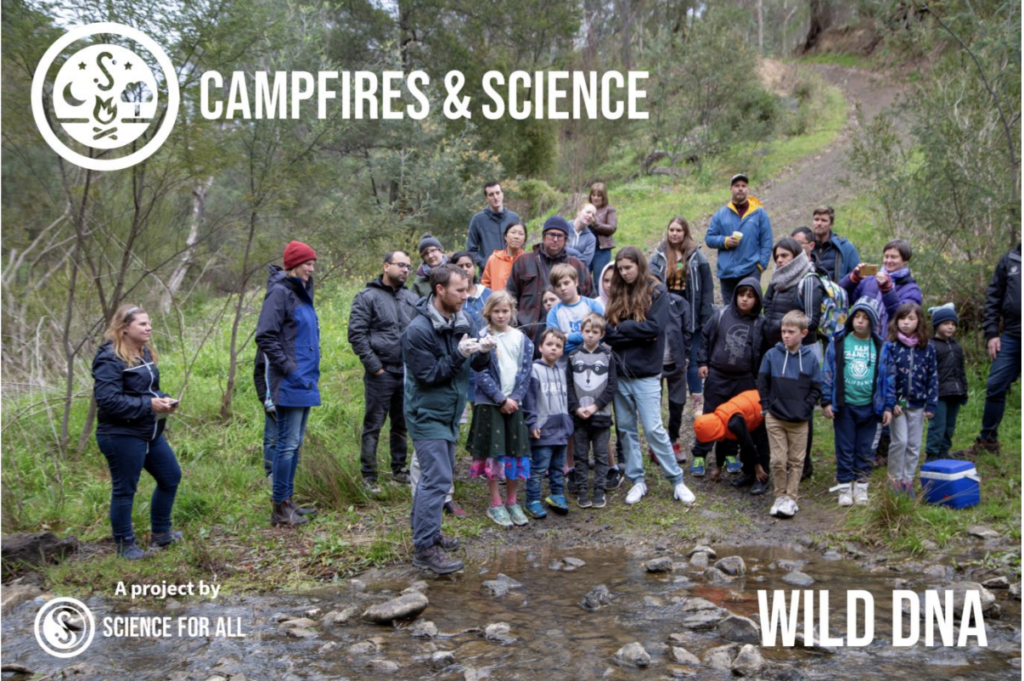

Involving the public in helping understand and restore natural heritage will be central to the success of any effort to prevent further extinction. Science for All runs free ‘Campfires and Science’ events at which people of all ages and backgrounds are invited to gather around a campfire to learn from experts on how to get involved in understanding and restoring biodiversity. Since their inception, they have trained hundreds of people to perform biodiversity surveys and have co-created novel species detection methods using environmental DNA.

Environmental DNA is the traces of DNA in cells left behind by an animal in its habitat. Water from a river or soil from the ground can be used to find these cells, from which DNA can be extracted, acting as evidence of the presence of animals in the wild.

Science for All explores novel ways of involving the public in this process – including training people to use DNA testing to look for traces of endangered animals in the wild through their project, ‘Wild DNA’. The project works in partnership with experts in conservation and environmental DNA, Aboriginal elders, and members of the community towards a common goal: understanding how to improve our biodiversity.

In partnership with the community lab, BioQuisitive, Science for All has worked with members of the community to create DNA detection methods that are cheaper, quicker, and easier so that they can be adopted by anyone who wants to give them a go. Sampling and monitoring current populations of native species creates baseline data of what biodiversity we have. From that baseline, it is possible to ascertain the impact of both positive and negative interventions, such as tree-planting or cutting trees down and burning habitat.

“To date, there has been little evidence of population restoration because we simply cannot accurately determine where populations of endangered species currently sit,” says Jack Nunn, Director and Founder of Science for All. “Our dream is to involve the public in collecting data to support evidence-based environmental management.”

To date, the ‘Wild DNA’ project has worked across the Central Highlands of Victoria in Marysville, Yellingo, and Toolangi looking for four different endangered species: Greater Glider, Leadbeater Possum, Barred Galaxias fish and the Helmeted Honey Eater. Members of the community were taught to detect environmental DNA in soil samples, use thermal imaging cameras, and use mosquito traps to test for the DNA of these endangered species in mosquitos (i.e. if the mosquitos had bitten the animals and taken their blood, their DNA would be present).

Science for All have also run a number of metropolitan ‘Campfires and Science’ events. They’ve worked with Whittlesea Tech School at Plenty Gorge to search for platypuses using portable DNA testing kits, and used drones and thermal imaging cameras to spot critically-endangered animals. Along the Kororoit Creek, they worked in partnership with local communities to plant trees and native grasses, and used environmental DNA testing and microscopes to explore the life found in and around the creek.

World-first DNA test

As part of the ‘Wild DNA’ project, new types of DNA tests were developed to sequence the DNA of Leadbeater Possums in partnership with experts from Monash University. These tests use ‘primers’, which are short fragments of nucleic acids that bind to known genes (sections of DNA) to provide a starting point for DNA sequencing. Primers currently exist that capture genes common to groups of animals (e.g. multiple marsupial families), but, according to Jack Nunn, “the dream is to get down to having species-specific primers”.

In a citizen science effort, the team designed primers that specifically target the mitochondrial DNA of Leadbeater Possums (DNA that exists in the mitochondria, separate to most of the genome). These primers are contained in an easy-to-use DNA sequencing kit for people to test soil samples for the presence of Leadbeater Possums in the trees above. The team has successfully isolated DNA from the soil in the Leadbeater Possum enclosure at Healesville Sanctuary and is now searching for the presence of Leadbeater Possums in the wild.

Species monitoring using environmental DNA sampling will help conservationists better protect our endangered species. The knowledge gained from this project will inform evidence-based management of natural heritage and help preserve Victoria’s unique biodiversity.

The knowledge and accessible biodiversity monitoring techniques developed by the Science for All community can be used by people around the world and will ensure that our unique biodiversity will remain for generations to come.

It’s our planet. Our knowledge. Our science.

Catriona Nguyen-Robertson